That terrible day

Moata recounts the events of 15 March 2019 as she experienced them (i.e. from the outside).

There have been many times in the last 5 years when I've thought about writing about my experience of being in Christchurch on the 15th of March 2019 - the day of the terror attacks on the Muslim community in our city - but I've been mindful of not centring myself in someone else's trauma, of not wanting to make it all about me when I am not much more than a bystander to someone else's tragedy. But as I mentioned in my post a couple of weeks ago, I do think it about it fairly regularly.

There is a sense that devastating events generate a sort of rippling, outwards moving wave, as in the manner of earthquakes. Some people are right at the awful epicentre of the thing, but there are radiating concentric circles of effects that move through a community (or communities), their intensity lessening as they move further from the devastation but still leaving their marks. So I'm in one of those circles farther out where the waves are small.

This is where my story sits. It's not the main story. It's not the most important. It's just mine1.

It was a Friday.

I was at work in an office in Sydenham. I usually shared this office with a colleague but she worked from a different building on Fridays so I was on my own. There was a small number of other colleagues in the building but I was alone when I started to see reports on Twitter of someone in Christchurch at large with a gun. Because mass shootings didn't happen in New Zealand, let alone Christchurch, I was not immediately alarmed by this. I sort of naively assumed that some idiot was being idiotic and would be bundled into a cop car in short order. Because until something terrible happens you don't really believe that it can. Until there's an earthquake/pandemic/terrorist with a semi-automatic it doesn't occur to you to be fearful of those things.

I don't remember exactly how long it was between "I'm sure this will be fine" and "Oh fuck, no" but the reports on Twitter got more worrying and I started to hear a LOT of sirens. I put my headphones on and tuned into RNZ to hear their coverage.

My son, at that time was 5 years old. He'd started school less than 2 months beforehand. It's such a big move into a wider world when kids start primary school. Preschool feels small and cosy by comparison and to start with you're just taking it on faith that they'll be safe and well in this larger, busier environment. They're still so little with their enormous backpacks and their brand new school uniforms.

So when I heard someone telling Jesse Mulligan on the radio that a gunman had fired on people at the Al Noor Mosque and that those shot had included children as young as four2, that's when I started sobbing. That's when I started being truly, gut-clenchingly fearful.

Not long after this I got messages from my co-parent that my son's school had been locked down. The school was a 5 minute walk from the Linwood Islamic Centre, the site of the second attack, and on the same main thoroughfare. I felt sick. I thought about the parents on 22 February 2011 who, because of traffic or transport issues, couldn't get to their children for several hours and how that might have felt a bit like this. The panic of not being able to get to your child and be assured of their safety is not a nice feeling even if you tell yourself quite reasonably that there's no reason to think they're in any danger. You need to know they're not. You need to see with your own eyes that they're not.

My colleagues and I were informed that our building was in lockdown as well. There was much frantic texting and tweeting to establish that people I knew were safe and my co-parent decided to go to the school where he and some other parents were corralled into the staff room to wait for the all clear. I was suddenly aware in a way that I never had been before, that my office was immediately next to the entrance to the building, and glass on three sides. There was absolutely nowhere to hide.

It was hours of waiting. I finally got to leave after 6pm, perhaps an hour after my son's father was given permission to collect him from his classroom and take him home. But not before he and some of his classmates got to use a bucket for a toilet. Which I think he thought was pretty cool. I am forever in awe of the teachers for keeping everyone calm when they themselves must have been feeling pretty freaked out. And for dealing with the bucket.

Being reunited with my child was the best feeling. Just the best fucking feeling. You hold your babies tight when you're confronted by the reality that some parents were never going to be able to do that again. Fuck.

Still, neither parent could be bothered doing anything much about dinner so we drove in a zombie-like state to the McDonalds in Woolston and sat there next to the play area, emotionally wrung out but also jumping at shadows. For a time I personally eyeballed every single person who came through the automatic doors of that McDonalds like my life depended on it, paying especial attention to white males. One woman walked in wearing a tracksuit jacket with "Australia" emblazoned across the back, and I guess we must have known by that point the nationality of the person responsible, because I had a minor panic until she was joined by her family. It's safe to say that I was hyper-vigilant to danger, which I assumed to be everywhere.

But even so, sometimes you just have to mechanically eat a Big Mac while watching your beloved, innocent 5 year old climb play equipment while similarly strung out Filipino and Chinese parents do the same. Just kids of various races chasing each other through coloured plastic tunnels completely unaware of the weight their parents are sitting with. If I were writing this as a work of fiction I'd call that scene a bit too obvious and on the nose. But what can I say? That's just what was happening in that corner of Christchurch on that particular evening.

Later that night as I was getting my kiddo ready for bed it became apparent that his dad had mentioned something about the reason why he had to stay inside the classroom for so long, but that he had got some things confused:

Where’s my parenting Oscar for keeping a neutral facial expression when my kid said “I think the bad guys at my school killed some kids” when actually I just wanted to crumble onto the floor?

— Madam Snazzy (@MoataTamaira) March 15, 2019

Truly, it was so hard to keep it together in this moment. As someone in the replies says they do not give you a manual for how to deal with this situation as a parent. In my entire educational life from primary school to post-grad I never had a single moment of having to be locked down due to an armed shooter being on the loose. My child went less than 2 months. I'm grateful the subsequent 5 years have been quiet in this regard.

The following days were strange and worrisome. I took the dog for a walk and got startled by a car squealing around a corner but breathed a huge sigh of relief when I saw that the driver and passenger were Polynesian. I "racially profiled" every white person I saw. I felt a sense of safety and community with any and every brown person I walked past. Because of the unspoken understanding. The knowledge that any of us might also be targets. Not this time, maybe. But sometime.

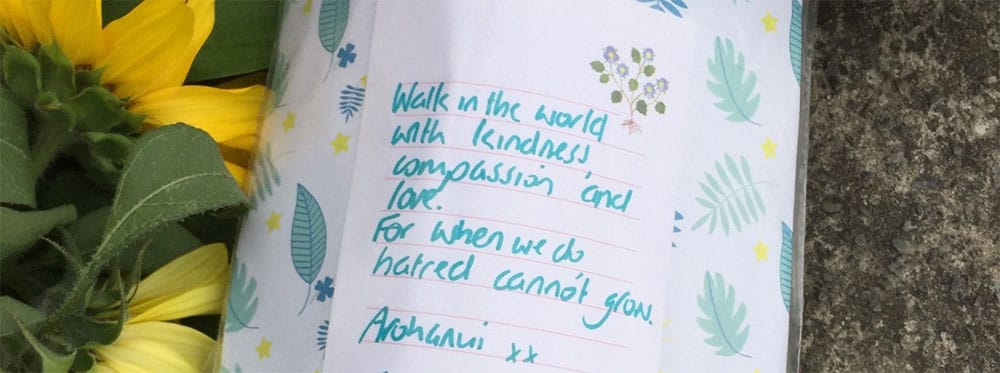

I walked down to the police cordon around the Linwood Islamic Centre, patrolled by very armed police officers, to find that people were leaving cards, toys and flowers gathered around traffic cones mourning the dead, expressing their bewildered grief.

At some point in the aftermath I must have watched some news footage because an image of the Imam of the local Islamic Centre standing on the street in a white gown with dark brown blood stains down the front of it is embedded in my brain. So much so that later that weekend as I am getting ready to have a shower, I look in the bathroom mirror and see a brown stain on my nightie from where I'd clumsily spilled some Milo I'd been drinking. In that moment I am overcome with panic and hastily wrestle the offending garment off myself and fling it into a corner like a woman possessed, breathing heavily and feeling sick. I have honestly never experienced anything like that before or since.

In the days that followed I was heartened that our then Prime Minister was an empathetic figure, resolute and humane. I miss feeling that.

I have never spoken the name of the person responsible for all that death and horror. Nor has anyone I know in Christchurch ever said it out loud to me. Which I cannot imagine is an accident. The only time I have ever heard it was on the news. Nor have I written it, nor do I intend to. He is simply That Person. I skim past his name in written accounts. He is not worthy of my thoughts. It takes a minor effort to do this - it gets easier as time goes on. This is my small act of defiance.

I don't really know how to end this. This is what happened but it's also a half-remembered thing that time has dulled a little. Did my life change that day? Only in quite subtle ways. Not anything that you'd particularly notice, but it's there still. My son picked up a cabbage tree leaf on our morning walk to school once and was pointing it like a gun, aiming it at cars, just metres from where the Islamic Centre had been and I was probably a bit too harsh with him about it. It's fair to say I overreacted. He's just a kid and he didn't know.

And I always hated guns anyway.

1 There are many accounts and lots of information about people who were much more directly affected. Here are some you might consider reading:

- Husna's Story: My wife, the Christchurch massacre & my journey to forgiveness by Farid Ahmed

- Christchurch mosque shootings: Terror victims tell their stories in their own words New Zealand Herald

- Brokenhearted, not broken: The scale of loss in the Christchurch mosque shootings Stuff interactive

- New Zealand mosque attack: Who were the victims? Al Jazeera

- The Christchurch Testimonies The Guardian

- Christchurch mosque terror attacks: Behind the scenes of meeting the survivors RNZ

2 The youngest victim, Mucaad Ibrahim, was three years old.